When Dawn Jackson made the transition from dance to film, she didn’t have to look far for a remarkable story, the recovery of fellow WAAPA-trained artist Floeur Alder after a life-altering attack. She spoke to Mark Naglazas.

Documenting a dance of recovery

10 August 2021

- Reading time • 8 minutesFilm

More like this

- How to watch ballet

- STRUT Dance comes of age

- Fairytale leaps to life with fun twist

On a Wednesday night in June of 2000 Perth dancer Floeur Alder was walking to her Highgate home when a man crossed the street and, without saying a word, plunged a knife into her face.

Alder managed to make it home and pull out the knife before staggering into Beaufort Street, blood spurting from her neck. An ambulance was called and the 22-year-old rushed to hospital, where she miraculously survived despite almost having her jugular vein severed.

While Alder recovered physically from the horrific injury with a barely visible scar the psychological wounds were not so easily patched up. She spent years coming to terms with the horrific experience, which impacted all areas of her life.

Alder eventually returned to her “happy place” – the rehearsal rooms and the stages she’d grown up with as the daughter of dance legends Lucette Aldous and Alan Alder – and set about rebuilding a life that had been shattered by a person whose identity remains unknown.

Alder’s remarkable journey of recovery has been documented by Perth dancer-turned-filmmaker Dawn Jackson, who has been close to Alder and her parents since studying at the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA) in the mid-1980s.

Jackson is now in the process of completing her hour-long documentary, Pointe: Dancing on the Knife’s Edge, that does not simply tell the story of the attack and recovery through dance but paints a portrait of an artistic family and the pressures associated with being the only daughter of dance royalty.

“Floeur recovered physically quite quickly but it was the struggle to overcome the emotional, psychological and spiritual trauma that made me want to tell her story,” Jackson tells me in a café not far from her Bicton home.

“The way we look at trauma today is totally different than we did 20 years ago. Back then victims of crime were given a little bit of counselling then basically left to their own devices. Now we know a lot more about post-traumatic stress disorder and the many triggers that can send someone back to that moment of horror. The body heals but a lot more has to happen for the soul to recover.”

Arts has a bigger role to play than just entertainment. It’s about its power to heal during times of trauma. It’s why the arts have never been so important.”

Jackson first encountered Alder while studying dance at WAAPA with Lucette Aldous and Alan Alder. Aldous, who’d retired from dance after a stellar international career dancing with the likes of Rudolf Nureyev, would bring young Floeur into the WAAPA studios, where she grew up immersed in the world of ballet.

Jackson said that studying dance at WAAPA in those early years had a wonderful family atmosphere fostered by Alder and Aldous (Alder passed away in 2019 and Aldous in June this year at the age of 82).

“Lucette and Alan were like parents for me,” says Jackson. “Floeur really took to my year. She joined us a trip to Hong Kong, which consolidated that bond.”

Their professional paths crossed over the years – Jackson choreographed a work for Floeur Alder at Strut Dance in the early 2000s – and when Jackson received the thumbs up from a panel of film industry experts for her pitch to tell the story of the vicious attack on the young dancer and her battle to rebuild her life.

Jackson was in the process of making a mid-career shift from dance to film – she’d won a prize for a short she made while studying at the WA Screen Academy in 2014 – and believed Alder’s story of recovery would be just the kind of arts narrative that would have appeal to a wider audience.

Working closely with Alder, who was anxious for as many people as possible to hear her story, Jackson has gone back to that terrible evening and then followed the dancer’s journey of recovery and the impact on her personal and professional lives.

“What’s so interesting about Floeur’s story is that she not only had to overcome the trauma of the attack, she was also fighting to come out of the shadow of her parents. You can only imagine what it must have been for a young dancer desperate for her own artistic identity when the names of her famous parents come up in every conversation.”

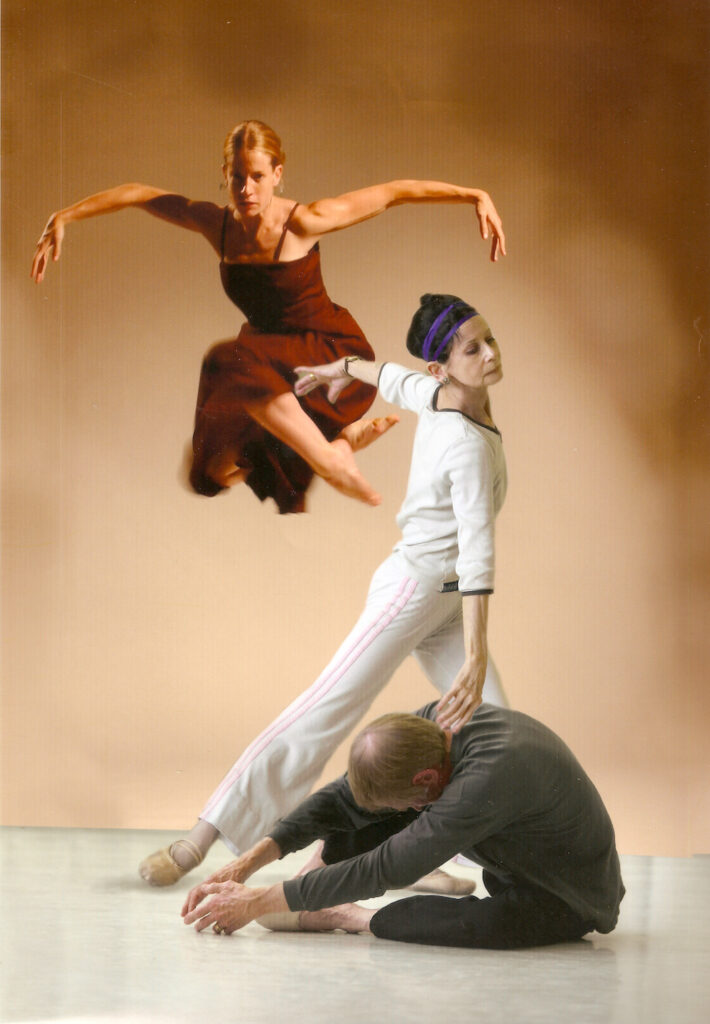

A key chapter in that journey was Floeur’s work Rare Earth, which she choreographed for her parents to perform with her in 2004. The work, which was later performed as part of WAAPA’s 25th anniversary celebrations, saw her coach her classically trained parents to utilise more contemporary approaches and techniques.

“From that I realised there was something truly interesting here. I wanted to tell the story of how Floeur not only overcame the trauma of the attack but how she came to face and embrace her legacy instead of trying to resist or run away from it,” says Jackson.

Jackson has finished filming for Pointe: Dancing on the Knife’s Edge and has a distributor for the film but still needs funds to complete post-production. Several high profile Western Australian philanthropists have invested but more funds are needed to finish her passion project.

“The digital-era disruption has made it more difficult for long-form arts documentaries to be funded and distributed,” says Jackson. “But I believe there’s still a great hunger for narratives that both celebrate an artist and their work at the same time as telling a universal story.

“Returning to dance saved Floeur,” she says. “This is why the threat to the arts through lack of funding is so short-sighted. Arts has a bigger role to play than just entertainment. It’s about its power to heal during times of trauma. It’s why the arts have never been so important.”

If you wish to help Dawn Jackson complete Pointe: Dancing on the Knife’s Edge go to the Documentary Foundation Australia.

Pictured top L-R are Lucette Aldous, Floeur Alder and Alan Alder performing ‘Rare Earth’.

18 August 2021: Originally this article suggested that Floeur Alder’s attacker was drunk. This was not the case and the article as been amended to reflect that.

Like what you're reading? Support Seesaw.