A local artist with an international reputation, Erin Coates is known for making works that are at once unsettling and compelling.

Diving into the gothic world of Erin Coates

22 September 2023

- Reading time • 10 minutesVisual Art

More like this

- Waves of influence span an ocean

- A walk with Tina Stefanou

- A blaze of glorious people

There’s something Frankenstein-like about Erin Coates’ creations, which mash human forms with other life forms, often in underwater settings.

In the last few years Coates’ works – which range across drawing, sculpture and film – have been seen in many WA galleries, including the Art Gallery of Western Australia, Moore Contemporary, Holmes à Court Gallery, PS Art Space and Goolugatup Heathcote Gallery (for Perth Festival), as well as numerous interstate and overseas festivals and galleries.

Back in 2008, however, Coates was an emerging artist, freshly returned to Perth from living overseas and finding her way into the local scene. Selected to exhibit her work in the 2008 Joondalup Invitational Art Prize exhibition – the City of Joondalup’s major acquisitive art prize for professional artists – she had no expectations of winning. So when her name was called she was so unprepared she had to be prompted by a friend to go on stage to receive the prize.

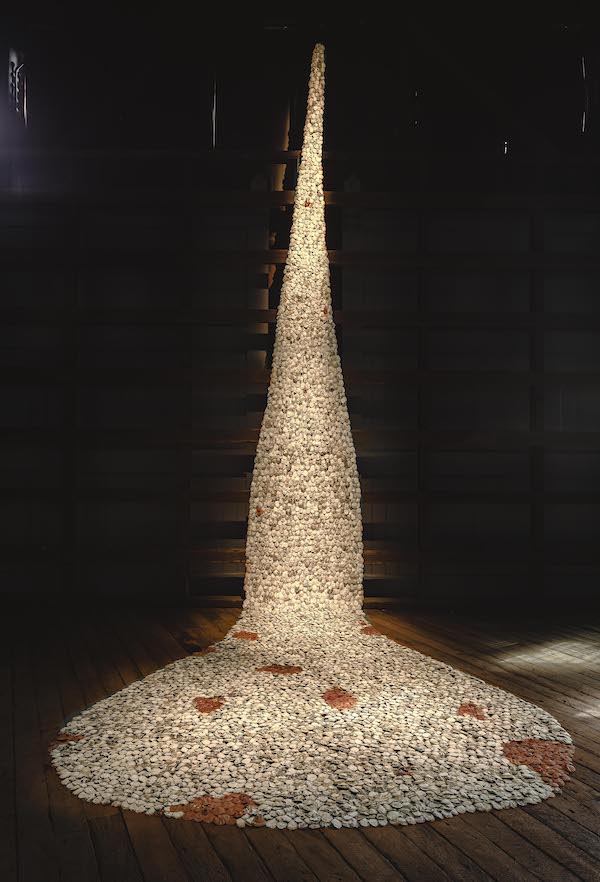

Fifteen years on, Coates’ winning work, Microeconomics (paradise spent), will be displayed again, when the City of Joondalup celebrates the 25th anniversary of its Invitation Art Prize by showcasing the previous 25 winning artworks.

Ahead of the exhibition’s opening Nina Levy chatted to Erin Coates to find out what winning the prize meant to her, and how her work continues to evolve over time.

Nina Levy: You won the City of Joondalup Invitational Art Prize in 2008. What was happening in your world at the time that you made the winning work, Microeconomics (paradise spent)?

Erin Coates: I was very much an early career artist. I’d spent most of my twenties living in Europe and then doing my MFA in Canada – the time away was great, but it meant I came home and had no profile, networks or really any opportunities in the arts in WA. I was working in multiple part-time jobs, and as the ARI scene was yet to take off, I was organising shows in informal spaces and working on building up my own creative community. In this sense, it was a period in my life that was hard work, experimental, grungy and a lot of fun.

NL: What was it like to win a major award at that early stage of your career?

EC: Winning was utterly surprising. When my name was called out at the opening I thought I was having some kind of dissociative aural hallucination and my friend had to literally push me up on stage.

It was an incredible boon to my creative practice. I was working so hard, often with the feeling of little traction, so it was very affirming to win and allowed me some breathing space from the grind of balancing various bits of precarious employment.

NL: Looking at your recent work, your practice has undergone significant shifts and changes in the intervening 15 years.

However, Microeconomics (paradise spent) – a “rewriting” of the centre panel of Hieronymous Bosch’s Garden of Unearthly Delights – feels like it contains foreshadowing elements, both of the direction of your work and of the direction of our society.

In particular there’s a gothic, unsettling feel to Microeconomics (paradise spent), a sensation that is present in your current work. How has your relationship to the gothic and horror evolved over time?

EC: I often draw from experiences in my own life and at the time of making that work I’d recently spent several years living abroad. I had been through a couple of quite horrific experiences, but I’d also had a rather hedonistic and enjoyable time. I was drawn to recreating that Bosch work, partly because I had a tonne of foreign coins, but mostly because it was a way of luring people in with seemingly pleasurable imagery while hiding these unsettling elements within the details.

In that sense, it parallels the approach in my recent work. I am interested in how horror can disrupt the everyday, and also give us a way through the darkness.

NL: Underwater worlds are centred in a number of your more recent works, informed by your research as a freediver. What is it about marine environments that moves you to make work?

EC: The impetus was a Spaced residency I did about 10 years ago in Albany – where I’d grown up – and I wanted to understand the whaling history there through a different lens, as well as my own experiences having a seafaring family.

There is an incredible allure to submerged spaces, and the ocean can be understood as both a physical place and a kind of psychological space. My recent work has been looking at marine ecologies whilst also exploring elements of my own life, though often in an encoded or indirect way.

NL: Your work was recently on display at Fremantle’s PS Art Space, in the group exhibition Walyalup Waters, which celebrated the power and beauty of Fremantle/Walyalup’s bodies of water.

Tell me about We’re always touching underwater, the work you were commissioned to make for that exhibition.

EC: It is a sequel of sorts to Alluvium, a short film I shot in the Derbarl Yerrigan a couple of years ago. This work heads out from the river mouth into the ocean around Walyalup.

We’re always touching underwater is an abstract horror film that uses the established trope of “the body in pieces”’ to examine environmental anxiety and the nature of loss. In it, we see a series of uncanny lifeforms interacting on the seafloor. It continues my interest in human-animal entanglements and is also an exploration of grief.

To make the film, I created a set of kinetic silicone props which at times are hard to distinguish from marine fauna. There is an intended unsettling beauty in the imagery and an element of dark absurdity.

NL: You work across drawing, sculpture and film, and you’ve shown work in both galleries and at film festivals – do you know from the outset which medium you are going to use to explore a particular idea, or is this something that you discover as you go?

EC: Drawing is foundational to my practice and often where I start. Ideas are sometimes better suited to installation or moving image though, if there is a certain expansive feel to the idea. I usually stay within the terrain of a concept and body of research for a while, and end up making works across drawing, sculpture and screen that become interconnected.

NL: What are you currently working on? What’s next for you?

EC: I have a residency with Art On The Move and the Museum of the Great Southern, taking place this year and next. I’m working on a private commission through Moore Contemporary and I’m in a show at QAG/GOMA later this year.

I also have some film works in development, on super slow burn – I have a rather epic approach to screen works in that I make all the props and sets and they are usually very hard to film (underwater, inside a car or scaling structures at dawn), so it can take a long time to shoot a work.

NL: Which artists’ works are you particularly looking forward to seeing at the City of Joondalup’s retrospective exhibition?

EC: Really, all of them! But if I were pushed to pick a few, I’d say the works by Brendan Van Hek, Teelah George, Emma Buswell and Jarrad Martyn.

You can also listen to an interview with Erin Coates as part of Marnie Richardson’s audio storytelling project The Mapping Exercise. Like Walyalup Waters, The Mapping Exercise was presented as part of Fremantle Festival’s 10 Nights in Port.

Pictured top: Erin with part of the set from ‘Dark Water’, a film by Erin Coates and Anna Nazzari. Photo: Michelle Becker

This article is sponsored content.

Seesaw offers Q&As as part of its suite of advertising and sponsored content options. For more information head to https://www.seesawmag.com.au/contact/advertise

Like what you're reading? Support Seesaw.